Dear Tech Buzzers,

Thanks so much for sticking with me through this year of experiments. I’d be curious as to your thoughts on the newsletter and what you think of it, as I decide how to optimize my time. As you can probably tell though, I am most interested in telling long-term stories and trends, and less sensitive to news and product announcements, and that bias has widened over time. Call it the value investor in me!

We will have one more episode of Tech Buzz and one more newsletter before the end of the year. Thanks for all of your support!

Best,

Rui

Internet Platforms: Antitrust Regulations are Here

Our very first episode of Tech Buzz captured an interesting coincidence: the same week that Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg apologized on Capitol Hill about data privacy, ByteDance’s CEO Zhang Yiming was making his own — arguably much more public — apology re: the shutdown of Neihanduanzi, a jokes and memes app and the company’s first creation. The circumstances weren’t all that similar, but the timing made for a fun contrast, I thought. Two and a half years later, I am finding many more such “coincidences.” A flurry of them occurred over just the last few weeks, all around the same theme —

-

Nov. 10, 2020. One day before Single’s Day, China’s SAMR (State Administration for Market Regulation) announced new draft rules for regulating anti-competitive behaviors at internet platforms.

-

On the same day, the European Union filed an antitrust suit against Amazon over use of data.

-

Dec. 9, 2020. The Federal Trade Commission and a coalition of attorneys general from 48 states and territories filed two separate antitrust lawsuits against Facebook.

SAMR’s new draft rules immediately wiped off more than $280Bn from the market caps of Chinese internet giants. I highly suggest you read the highlights summarized here. (The deepL translation of the entire document, by the way, is here.) But like many legal documents, it was both more specific than I expected in its definitions of terms but also very vague in what punitive actions were actually going to take place. Given that the rules were to apply to internet platform companies, it was encouraging to see that algorithms, for one, were included as one of the ways of reaching monopoly. The regulators were also smart to realize that markets may be hard to define in these new economy companies, and that monopolistic behaviors can be identified without defining the market. Big data discrimination and “either-or” exclusivity also made it into the document. But what exactly was going to happen? Would any transactions get unwound, businesses have to be spun off, or major fines levied? How could I find out more?

I hadn’t paid much attention to antitrust laws and regulations before, especially in China. But now I had a few questions that urgently needed answering. One, had I just completely missed all the signs that all these anti-trust rules were coming? Two, what is it with all of these things emerging at once? Was there some coordinated global anti-monopoly movement? Luckily, I was able to talk to Frank Fine, a very experienced EU antitrust lawyer (since 1986!) and Executive Director of the China Institute of International Antitrust and Investment (est. 2012). And here are some of what I found.

China Anti-trust

As it turns out, the answer to whether it had been obvious that China was going to enact tougher anti-trust laws was both yes and no. Yes, because there had been a lot of regulatory activity in this space, especially over the last year. But you could also argue that no, it would’ve been hard to notice because internet companies had not been publicly part of the conversation for a very long time. Here is what I mean.

The “yes” portion of the answer stems from the fact that back in January of 2020, there was already a Draft Revision to the “P.R.C. Anti-Monopoly Law” (Draft for Public Solicitation of Comments). (You can find an unofficial English translation on the excellent China Law Translate website.) In many ways, the most substantive portions of the regulations that would be unveiled in November were already set forth in this draft document. Furthermore, as many have noted*, this document was a legitimately big deal. It was the first substantive revision since the initial law passed over a decade ago, and furthermore, at 8 chapters and 64 articles to the document, it was 7 articles longer than the initial law and some would say that it was “comparable to issuing new legislation.”

Fast forward eight months to September 2020, when SAMR published an “Antitrust Compliance Guide for Operators“*. While this was a national-level guideline, it is important to note* that the province of Zhejiang (home of Alibaba) and the city of Shanghai, two of the richest places in China, had already published their own guidelines on this subject in the second half of 2019. Those documents were actually even more detailed and even assessed risk level of triggering antitrust investigations by job function. And they weren’t the only ones. Not to be outdone, the less wealthy provinces of Shandong, Henan, Hunan and Hubei also issued guidelines this year. However, you could argue that I could be forgiven for not noticing either of these — they were not specifically directed at internet companies.

There’s some context we should understand about the differences between the US and China. Where US antitrust regulations can be traced back to 1890, China’s first iteration of antitrust regulations were formally implemented only in 2008*. However, as has been widely acknowledged, these regulations have not been typically enforced against technology companies. While it is true* that investigations in industries as wide-ranging as liquor, to LED screens, to contact lenses were conducted, punishments delivered, acquisitions blocked, and once even a $100mm fine was levied against a consortium of dairy companies, no serious action had been taken against any internet company. In fact, there was really only one relevant case, the 3Q War, which we talked about on the podcast way back in Ep. 5, Has Tencent Lost Its Mojo. Because of the way that battle ended — with Tencent found innocent of monopolistic behaviors — you could say that it might have even given folks the idea that internet companies could get away with a lot. In fact, given its significance in Chinese internet history, I’m going to provide you a quick refresher on how this very first anti-monopoly case heard by the Supreme People’s Court went down:

Back in 2010, both Qihoo 360 and Tencent had products that were used by the vast majority of Chinese netizens. In Qihoo’s case, it was their antivirus software. For Tencent, it was QQ, an instant messaging program. Anyone who went online regularly in China probably used both products. However, Tencent decided to “invade” Qihoo’s home turf by releasing its own security software. This may not have been a problem if it did not bundle the program with QQ (via an automatic upgrade*), leading it to capture something like 40% of the market overnight. Qihoo retaliated by labeling Tencent’s programs as malicious and even releasing a product that targeted “QQ privacy abuses” specifically, resulting in Tencent stopping service of QQ on computers with 360 installed, alleging that such interference made it impossible to run its software as intended. Users were effectively forced to choose between the two products. The two companies went to court, and after an appeal argued in front of the Supreme Court, the judgment was ruled in Tencent’s favor — it had not in fact abused a monopolistic position.

Yes, quite incredulously, the court ruled that Tencent did not have a monopoly partly because the competitive market was global, and even companies like Facebook could be considered their competitor, despite everyone knowing that Zuck had exited the Chinese market years earlier. And while Tencent eventually won the legal battle, it seemed to have taken the public lashing it received to heart, heavily expanding its investments and partnerships instead of always competing directly with others. The 3Q War, by the way, has been blamed as one of the main reasons for Tencent’s “progressively unambitious strategic direction” (not my view per se, but a common sentiment), and is even believed by many to be why it’s losing time spent so quickly to newcomer ByteDance. But its effects on everyone else might have been the opposite. It seems that some of the internet platforms saw this as a free pass to be as anti-competitive as they can.

Some of these anti-competitive practices, which had been covered extensively in media in the last few years and were the subject of much consumer ire, included:

-

Discriminatory pricing: specifically, 大数据杀熟, which became an internet buzzword in 2018 when certain platforms were found to offer the same product or service for a higher price to users who had been on the platform longer, the logic I suppose being that their loyalty would make them less sensitive to price.

-

Either / or (二选一 “choose one of two”): typically referring to users or vendors having to choose exclusivity with one platform. Alibaba is one of the most often accused of abusing its monopoly position to demand exclusivity, and as late as last year, defended it as a standard market practice. The public derided them for this statement, but what can one do? As the clear market leader, there are very few alternatives.

-

Bundling (捆绑搭售): This was most frequently happening on travel platforms, when users would be misled or coerced into buying insurance or other services they didn’t need. I saw this firsthand whenever I used Ctrip, for example. While new ecommerce regulations passed on Jan. 1 2019 explicitly forbade this, the behavior has only diminished*, not disappeared altogether.

-

VIE entity monopolies: In July, 2020, for the first time, a monopoly investigation against entities with a VIE structure (the still “gray” variable interest entity formula used by many Chinese internet companies) was approved. It was heralded as a milestone case*, because even though there had never been any explicit legal wording stating such, it had been widely accepted in practice that monopoly cases against VIE were futile.

But the new November regulations made it clear: discriminatory pricing and exclusivity were valid bases for investigation, and VIEs were definitely not protected from complaint. (Bundling was already forbidden.)

Notably, on the same day, the Central Internet Information Office, the State Administration of Market Supervision, and the State Administration of Taxation jointly held an administrative guidance meeting on “regulating the online economic order.” 27 internet companies attended, and the theme was “unfair competition and monopolistic behaviors by online platforms.” Furthermore, the week after, 17 ministries and commissions of the central government have established a joint inter-ministerial meeting system to combat unfair competition (Central Internet Information Office, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, the People’s Bank of China, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), and the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) are among those included). “The government means serious business,” everyone said. They aren’t playing around.

Protect Small Business?

While the draft rules clearly say in its introduction that they are issued for the protection of “consumers and public interests,” realistically, the ones for whom some of these anticompetitive practices prove an existential dilemma are small businesses. This perhaps accounts for why much of the coverage on these guidelines attribute* their timing to COVID-19. The pandemic, you see, is hurting small businesses disproportionately. That much is irrefutable. With the platform companies dictating so much business in China, the government saw the need to step in and protect the micro-enterprise, the voiceless Davids against Goliath. It’s in line with what has always been said; the same arguments — minus COVID — were also used back in 2008*.

It is difficult to disagree. One of the points I’ve been making since the inception of Tech Buzz but much more loudly and confidently this year is the highly digitized nature of the Chinese (consumer) economy. The deep penetration of ecommerce (larger than the next 9 markets combined) and mobile payments (3x that of the US) is yesterday’s news. Combined with the rush of automation led by artificial intelligence, and the physical restrictions imposed by COVID, even seemingly unassailable processes such as physical signatures and company stamps are now — finally! — being abandoned. (One of the leading startups in e-signatures, eSign, just raised a $151mm Series D.) The reality is that for any new and even existing small businesses, there is no way to carve out an existence completely independent of the internet platforms. And any who attempt to do so wouldn’t get very far. But in negotiations with these platform companies are for the most part highly skewed in favor of the platform. For many businesses, “going online” has not yielded riches beyond measure. In other words, much of the gains unleashed by technology have gone straight into these platform companies — and more specifically, the pockets of their founders — not the small businesses who are supposed to be the economy’s “lifeblood.”

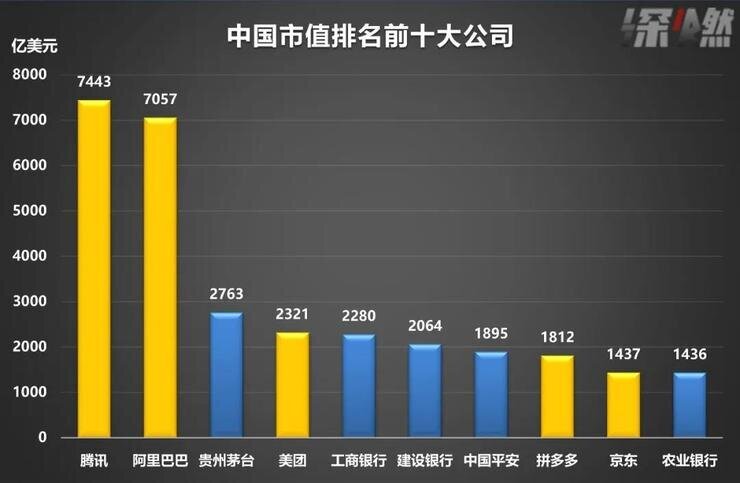

As I shared on Twitter last week, 5 of China’s top 10 listed companies by market cap are internet companies. And the top two — Tencent and Alibaba — dwarf the others by quite a big. (Number three Guizhou Maotai, the country’s premier liquor company, is often dismissed as being a bubble. “China’s $TSLA” is how a friend refers to it, a moniker I’ve since adopted.) Of the five non-tech companies, three are state-owned banks, and one is Ping An Corporation, the largest insurance company, trying desperately to mold itself into a tech company, as evidenced by its many tech-inspired spinoffs. So if nothing but just from a purely “most valuable companies” perspective, the internet giants were too high-flying to not warrant being paid much more attention.

Rui Ma 马睿

@ruima

Already knew tech dominates but wow.

As of Nov. 13, 2020, the top 10 Chinese companies by market cap (in $00s of millions USD):

1. Tencent

2. Alibaba

3. Maotai (liquor)

4. Meituan

5. ICBC (bank)

6. CCB (bank)

7. Ping An (insurance)

8. Pinduoduo

9. JD

10. Agricultural Bank https://t.co/yYZQDoRb9j

9:52 AM – 1 Dec 2020

Government vs. Internet giants?

As with anything in China, there is always the specter of government control for the sake of control. But at least in the case of these antitrust laws, it doesn’t seem to be a sufficient answer. First of all, as Frank tells me, Chinese regulators have been working on expanding antitrust laws as it relates to the internet space for at least the last four years, so this document does not come as any surprise. Furthermore, as made obvious by the beginning of this newsletter, which laid out the actions ongoing against internet giants in both the EU and US, it’s clearly not just the Chinese government, but world governments as a whole, who feel compelled to “do something.” At the very least, this does not seem to be at all related to the Ant IPO pull I wrote about last time, even though I will freely admit that that’s where my thoughts wandered to — the announcement did take place the day before Single’s Day, right? And given how Alibaba was one of the hardest hit, was this the government vs. Jack Ma, Round 2? But no, not really.

As Frank explains, the idea is not to cripple the existing internet platforms, but to provide inducements for others to compete. While I do not think that is currently as big of a problem in China internet with every major player jumping into every new trend, I can see how this could be a concern anyway, since most major battles do tend to still end up in a merger or acquisition, or alliances close enough as to basically cement existing monopolies versus create room for new platforms, as we see ad nauseum with Tencent vs. Alibaba. The legislation is just a first step to creating the proper legal framework to oversee that, since as you now know, VIE structures (and thus by extension really all of Chinese internet) had been pretty much exempt from scrutiny until now, with the exception of the 3Q War. It is not a “tearing down,” but a sort of “slow down.“ But how will the slowing down happen? Even if the intent is clear — we the government are now looking closely at your actions and have incorporated a significant number of new behaviors into our rules as legal basis for complaint — what can actually be done? A takedown? A roughing up? A big fine?

What’s Next

Which brings us to the question of “remedies.” Fines have not been particularly effective, even when they’re in the billions. So what else? Will key acquisitions from years prior be investigated and unwound, for example, like the current proposal for Facebook to divest Instagram and WhatsApp? Unlikely. That’s because as much as many of these platforms have been abusive in their customer and merchant relationships, wiping them out would be even more disastrous, so powerfully embedded they are now in daily economic (and emotional!) life. So the best case scenario, in Frank’s opinion, is making it much harder for the platforms to expand exponentially via acquisition in the future, versus trying to undo what’s already happened in the past. The worst case scenario is that nothing much happens, because the pandemic has highlighted how highly valuable these companies are to the smooth functioning of entire economies, and it is very, very difficult to balance the need for technological dominance and economic prosperity against the need for regulating monopoly power, which has been shown to accrue so easily and naturally to platform companies.

But let’s not downplay what the government is doing here. Just today, it has elevated the problem of antitrust into the annual economic work* of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. It specifically recommends the government to “strengthen anti-monopoly measures and prevent disorderly expansion of capital.” As I’ve said earlier, the government is serious about this. And as you might expect, anti-monopoly experts and advisors tout it as a catalyst for further economic reform and opening up*. It is true. The old days of saying “China needs to strengthen monopolies” because Chinese enterprises used to be so small are far behind us. Chinese companies (including Hong Kong) now outnumber American ones on the Fortune 500. They don’t need to be “protected.” The market needs protection from them. To take a close from relatively recent memory, if things were working properly, the Didi and Uber China merger would’ve been much more closely scrutinized, instead of being met with silence like it did. That deal obviously changed completely the dynamics of the entire ride hailing market in China. Should it have been stopped? I guess we’ll never know.

So the TL;DR is that I have no idea what enforcement will actually look like, but reversing prior transactions and hobbling current giants are unlikely. It is much more probable that the largest are more scrutinized and their growth “capped” while smaller platforms are still given ample room to grow, resulting in what a friend has termed a “collective win” for the Chinese internet sector rather than individual 800-lb gorrillas. This is probably not surprising to most of you. On a macro level, the last decade has apparently seen China shift its focus from topline-growth at all costs, to a more balanced sort of growth that is lower risk and more equally beneficial to all segments of society. It would make sense, of course, since we have all seen how inequality can lead to social instability. But specifically, such measures can include making sure new businesses, for example fintech, do not become a new breed of “too big to fail.” And they are not alone. I am still not very well-read on this subject, but everything — including the Antitrust Institute that Frank directs — shows me that there is a global conversation happening. If not directly — the senior antitrust advisor & researcher in China I quote above studied abroad and is deeply influenced by his European and American mentors — then at least indirectly, via studying foreign cases. Even all the layman’s articles on antitrust I read would mention the basics of US law in this area as well as point to the many closed and pending cases against foreign tech companies.

But those of you with investments in these Chinese tech companies. Don’t worry. The corporations are not sitting idly by and have been forging their strategy for years, knowing that this would be coming. They are actively hiring from the revolving door of antitrust regulators whose political ambitions have expired for one reason or another and are open to working in private industry*. The general direction can’t be changed, but the blows can certainly be softened. Good luck!