Extra Buzz 011: Kuaishou Strikes At Bytedance’s TikTok with Zynn

Hi Extra Buzzers,

As mentioned, I’m making up for missing an Extra Buzz issue and so that’s why you’re getting me two weeks in a row! This week is a good example of why I chose the initial biweekly format in the first place – while there is always a ton of news and headlines in the Chinese tech ecosystem, unless you want to chase after every little thing that’s happening, there simply isn’t enough “earth-shaking” news IMO for the non-China-exclusive specialists amongst us for a weekly cadence to be comfortable. And that’s my long-winded way of saying nothing of great importance happened really. The only thing that caught my eye that I think might be of interest to you is the rise of Kuaishou’s TikTok clone Zynn to the top of the Apple Appstore, which I first saw reported in The Information. And so that’s what we’ll be discussing today. Zynn’s current claim-to-fame is that it pays you for actions completed within the app, whether it be simply watching videos or recruiting new users. Does this sound familiar to you? You bet! We have covered multiple versions of this tactic on Tech Buzz before, including Kuaishou’s own mainland efforts in Episode 55, and more recently, in Episode 67, Bytedance’s.

A bit of housekeeping before we get into the meat of it – as mentioned, I’m working on a short e-book on Bytedance to be released … hopefully not too long from now (fingers crossed!). That means we’re doing less of our own independent deep-dives for a while and relying more on our expert friends. If you missed our webinars, some of them will get made into podcast episodes, so you can always wait for those, but they’re also already available online on our YouTube channel:

And now, for the main commentary.

Best,

Rui & Ying

Kuaishou Strikes At Bytedance’s TikTok with Zynn

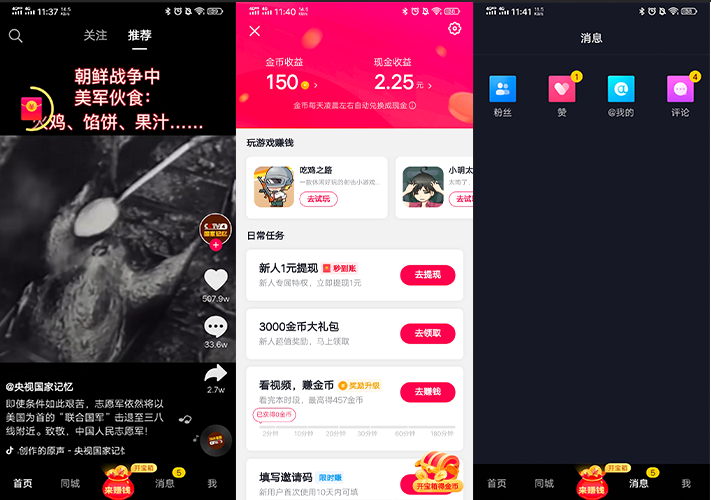

As far as I can tell, Bytedance nemesis Kuaishou’s Zynn app was launched in the beginning of May (SensorTower shows its earliest user review as May 7, 2020) and as of May 27, became the top-ranking Free App on Apple, a spot it continues to occupy today. This Twitter thread from VC Turner Novak shows some screenshots of the main mechanisms of the app, but as he notes, it’s basically a “dumbed down TikTok” and users get paid for their in-app activity, with the most lucrative action being “invite your friends.” Based on this, it’s pretty easy to understand why some people would liken it to a multi-level-marketing / direct sales pyramid scheme.

What it really is, of course, as I’ve already hinted at above, is just the latest take on the genre of “get-paid-to-use-our-app” … apps, some of which are more “legit” than others – i.e. you’re usually doing some work, like taking a survey or playing a game. Few are like Zynn, where the pay is purely for customer acquisition and retention within the app itself and not an indirect way of paying for services rendered. But not when you look in China. In China, there’s been a whole slew of these apps in the past few years, and here are a few reasons why:

Slowing growth in new mobile users led to sky-high acquisition costs. Since this varies across business models and sectors, I cannot give you a representative number, but here is one (very egregious) example: JD’s per capita customer acquisition costs went up 10x from 2016-2018, to over $200. Alibaba’s more than doubled from 2015-2018. I bring up this point because if you remember, one of the main reasons Bytedance Zhang Yiming gives for his success is the growth in smartphone shipments from roughly 2011 to 2017. As China’s mobile internet user growth declined and the market reached saturation, of course CAC went up. Irrational spending and an overheated fundraising environment propped it up further, of course, but there is no denying the role that slowing growth can play. Which is why you’ll find that a lot of the companies who are being creative with customer acquisition started around the end of this growth period, ie Qutoutiao in 2016.

Due to ubiquitous digital wallets, cash rewards AKA red packets were already being given out to encourage certain user behaviors, push installations, and the like. Longtime listeners will remember our episode on WeChat red packets, which didn’t start off with the company giving away money, but quickly evolved into cash giveaways by Tencent itself or basically any other Chinese company, internet or not, looking for more customers. This was as early as 2014. Of course, cash giveaways existed even before, but the ubiquity of WeChat (and Alipay) wallets certainly helped in their adoption. Practically everyone had their bank account linked now – there was simply no reason not to use this channel.

There are a lot of poor users in China. There, I’ve said it. Bluntly. But it’s true. The Chinese government reiterated it just last week as well: 40% of Chinese people – that’s 600 million folks – live on a monthly income of $140 or less, that’s $5 or less a day. The “third-tier city and below” population of a billion or so souls is what I’ve been calling “rural China” and their lives and interests can be very different from those in the first and second-tier cities, which are indistinguishable from many top global metropolises. They are the main force behind the rise of Pinduoduo, Kuaishou itself, and of course, Qutoutiao. And in the last two years or so, I’d say that the relentless search for new customers has led Chinese internet companies to well-beyond-fifth-ring-road to even fifth-tier cities and below. In Chinese media, this is always called 下沉 (sinking below). And it’s the perfect soil for these apps. In fact, maybe it’s the only thing that grows (well) – see my next point.

There is probably nothing better than money to motivate / teach new behaviors to less sophisticated users for which very few things are intuitive / natural. Yes, there is the obvious fact that for these people, every cent counts, but also, think about the actual “tech literacy” of this group of people. I don’t have the deep experience working with the very poor in China that some of my social worker friends do, but for five years, I ran a scholarship deep in the mountains for 100 impoverished kids. I wrote them regularly, visited annually, and got to know a few of their families. A lot of things we take for granted and understand about the internet (and modern urban life!) are not familiar nor intuitive to them. You really need to sit down and teach them. Yes, you can design all the bots and gamification triggers you want, and they might work, but nothing is going to work as well as a cash reward / hongbao (red packet) to train a user who otherwise has not ever experienced and therefore probably couldn’t even imagine some of the things you’re trying to introduce to them.

For rural users especially, everything is more social, including app discovery. So, in rural China, social networks are strong. Sharing is caring. Tapping into this and further incentivizing you to invite your friends to join you and “make some money together”? Help me make some money, we’ll do more business down the road? That’s very much how the community works.

Therefore, at least in China, as long as you have decided to go after “rural users,” the “lower” you want to penetrate, the more it makes sense for you to use cash payment as an acquisition tactic. Note, I don’t personally like the word “lower,” but it is a direct translation of the Chinese words used and I welcome suggestions for less loaded phrasing.

But in China, there is an additional wrinkle, which I think falls easily out of the points I make above, and that is the fact that these apps, which are generally called AppName+极速版 or AppName “Super Speedy” as I’ve translated in the past, are actually “Lite” versions of the main app. They exist mostly on Android, and are smaller in size and reduced in function compared to the “main app.” They also often have different slogans. And the reason is simple – this is just practical user segmentation. The poorer the mobile internet user, the more likely they are to be on a more primitive device (certainly not an Apple, so no iOS versions), where the reduction in app size and complexity actually matters. Yes, believe it or not, there are still 32Gb smartphones, and these aren’t even the cheapest. In rural China, nearly one-sixth of users are on phones that cost $140 or less. You can Google what that could get you. With these device constraints and likely different user habits / behaviors, it makes sense then that you would strip away certain functionality – not only would your users’ phones not be able to handle it, they are probably unlikely to want to use it, or even figure out how. Coupled with that, of course, is an entirely different marketing campaign which would of course use different slogans too – something perhaps more direct than the more highbrow sentiments you might be trying to promote with your “main app.”

So that’s exactly what happened in China. As of the end of 2019, there are no less than 75 such “Lite” apps in China, across basically all the major products you can think of – Baidu, Netease, 360, Weibo, iQiyi … name a major Chinese app with broad-based appeal that could benefit from “sinking into the lower-tiered population,” and you’ll find a “Lite” version. Of course, not all of them pay cash. All of them do have the reduced function and reduced size, however, as you can see from the table below.

Table comparing some popular "main" and "Lite" apps.

These metrics are taken from the Tencent My App Android appstore (AKA QQ Appstore, which is #1 in China at 26% market share). From left to right, size of app, ratings and downloads and corresponding slogans, are all as of April 2020. It’s pretty self-explanatory and so I won’t bother translating them, but you can see that there is generally a large dropoff in terms of size for most of the apps, by a factor of nearly 4 for Toutiao for example (first row) and more than 2 for Kuaishou (5th). Again, that’s because functions have been eliminated or greatly pared down.

An incomplete matrix showing just how many "Lite" apps there are. Gray represents investments.

As I said, not all of them pay cash. But a lot of the media ones do. That’s probably because of Qutoutiao, the Toutiao clone founded in 2016 (and IPO’ed in late 2018) that became known for paying its users to use its app, the exact same mechanisms, more or less, as Zynn. We went and visited the company last October as part of our Investor Trip. It’s not done well and is barely holding onto an $800mm market cap. There are many reasons but at least one of them is the emergence of a large number of well-funded, very large competitors, Bytedance being one of them. Surprisingly, it took them until September 2018 to react, but react they did, and Toutiao Lite went online. It crushed Qutoutiao. But the selling point was exactly the same – read news, get paid. Since imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, Tencent News went ahead and published its own Lite version a few months later in early 2019. And as I said above, you know now that both Kuaishou and Douyin launched Lite versions as well last year, Kuaishou in July 2019 and Douyin a month later.

If you’re a loyal Tech Buzz listener, you probably know also that we’ve called Kuaishou the “anti-Douyin,” although as their user bases get into the hundreds of millions, there is inevitably a lot of overlap. But still, the consensus is that the two apps generally represent two different user personas – Douyin (TikTok) being the more urban, hip and beautiful, and Kuaishou being the more rural, earnest and authentic. I think this kind of explains this graph, which is the estimated gap in DAU between Kuaishou (yellow) and Douyin (teal) Lite versions. Despite having a much lower overall DAU (Douyin was probably leading by 100mm DAU or so mid-2019 to Kuaishou’s 200MM+), Douyin Lite was nearly 50% below Kuaishou Lite as of the beginning of this year. My theory would be because Kuaishou had a better penetration / better understanding and handling of the rural audience for which Lite versions are best suited. Douyin will likely catch up (or maybe has caught up), but Kuaishou’s early lead is interesting for this reason.

Douyin Lite (teal) vs Kuaishou Lite (yellow) DAU through Jan 2020.

You’re probably seeing where I’m going with Zynn and TikTok.

Zynn looks like it’s TikTok Lite. Yes, even the size, which is half of TikTok’s 397Mb. (And that’s not because Kuaishou is somehow more efficient, because its flagship app is even larger at 438Mb.) It’s not as pared down as Douyin Lite, which doesn’t even allow for you to record videos and only lets you view videos, but it’s going in that direction. Its recording function is significantly simpler than TikTok, for example, which probably explains a lot of the difference in software size. However, in many other things seems to be trying to clone TikTok, pixel-for-pixel, as people have said. Including its appeal towards Gen Z, as evident by its marketing materials and overall look-and-feel. But people are not downloading it because it’s cool – most seem to be doing it for the money. As would be expected when you use a gimmick like that! You can see it for yourself, the comments inside the app are mostly spam, and external reviews, comments, and other UGC media about Zynn (ie YouTube videos and Reddit posts) are mostly of people talking about how to take advantage of the app’s cash giveaways, using their own referral codes of course.

Let’s see … the whole pay-to-use genre has been seemingly successful so far, with Qutoutiao publicly listed and Kuaishou Lite having achieved an MAU of 83mm in February. Or has it? Qutoutiao’s earnings from pre-covid Q4 2019 shows that its sales & marketing expenses, under which the cash payment “loyalty program” is categorized, was still over 80% of revenues, although that is better than earlier in the year when it was over 100%. Anyway, the company is under short seller pressure for faking revenues so there’s that, but I am just noting that even after three years, it’s yet to make a serious climb into profitability. As for Kuaishou Lite, it’s impossible to know how many of those users overlap with Kuaishou’s main app, so while press releases simply add them together as if they are distinct, many people, including myself, doubt that reflects reality.

So I think where I land is this: there are good reasons for the creation of the “Lite” strategy in China. I’ve listed them above. It doesn’t seem to make much sense entirely standalone, at least not until the cash payouts become a lot cheaper, relative to revenues. Maybe it makes sense as part of a larger company, too, but mostly I think it only makes sense if literally all your competitors are doing it, and the last part of the audience you’re missing is the part that’s so price-sensitive and difficult to reach / motivate / influence that this arithmetically becomes your cheapest, most efficient option. Like in fifth-tier city and below China, or something like that.

The greatly pared down UI for Douyin Lite. You can only view videos and the central focus is to get red packets …

Are any of these things true of Zynn? Well, it is not standalone … it’s got the backing of Kuaishou, which supposedly made $7.2Bn in revenues last year. I don’t know if I believe the number when an earlier estimate had been just $4Bn, but what is confirmed is that it raised $3Bn in December 2019, $2Bn of which is from Tencent, one of the best backers you can have, strategically and financially. So it’s got money to play with. But why is it taking a strategy that works well with its poorest customers in China and unleashing it on the developed world? Is it purely because of covid and the millions of unemployed? Are they trying to just get the teenagers who are looking for pocket money? And if so, does the current system make sense? It takes watching a few videos to get 0.6 cents on average … that’s right, a fraction of a penny. While new user activations start at $6, it requires the new user to be active. Kuaishou and Douyin Lite versions also have this, but focus more on continued daily logins, rewarding up to $0.67 on your 30th-day-streak, so you can see that they’re trying to build habits (and game their DAUs, obviously), but Zynn doesn’t seem to have this built in (yet)? Why’s that? And lastly, when the primary value proposition of the app becomes to “make money,” versus entertain yourself and make some money, as an afterthought of sorts … is that what you want? Then it becomes work, not entertainment, not the reward that Zynn wants you to associate with the app (and is trying to reference in its slogan!).

Of course this is just Zynn v1.0, and who knows, it may evolve very quickly. This is Kuaishou, after all, who has a much longer history in short video than even Bytedance (the app came online in 2013). It has also had its sights on the US forever, losing out to Bytedance on the acquisition of musical.ly (there is an oft-repeated rumor here of how that happened) and also mostly failing at international expansion, but not for lack of trying. So the will to globalize is absolutely there, and strengthened, I’m sure, by TikTok’s success. But has it found the way? Personally, I have trouble seeing how it could be Zynn, without significant modification anyway. But who knows, luxury brand Celine doesn’t seem to want to wait to find out, and if enough advertisers feel the same way, maybe all the cool kids will be Zynning next year. I just doubt it, that’s all.

But just in case … my referral code is UJ9K95F.